Users Who Spiked

EAT SH*T

Private Notes

Private Notes

Notes

Coprophagy. It's the scientific term for the eating of feces (It's also a good term to strike off your "things to Google" list). Although it's behavior rather repellant to most of us, there are several reasons why it exists. In fact, we'd all literally be in deep sh*t without coprophagy. So, who consumes dung, why is it eaten, and why in the hell would I want to write an article on the topic?

Several years ago, I was briefly the owner of a rather ill-fated Dalmatian. She was the first dog I had ever shared a home with. She introduced me to some of the gross realities of dog ownership. I also had a cat and it was all I could do to keep my dog out of the litter box. I think the most common familiarity people have with coprophagy is via their dog's behavior. So, despite the fact that dogs can just be downright gross at times, why would a dog want to eat its own (called autocoprophagy), another dog's (called allocoprophagy), or another species' (heterospecific coprophagy) poo?

A study done last year by scientists at UC Davis suggests that coprophagy could be an ancestrally inherited behavior meant to keep parasites out of the wolf den (Hart, 2018). Behavior modification training and anti-poo-eating meds didn't seem to have any effect, even on the most easily trained canines. The study also says that some dog owners hate this behavior so much that they consider euthanizing their dog. That's a behavior I personally find abhorrent. The Center for Canine Behavior Studies seems to agree with me. Their mission is to essentially "take a bite out of euthanasia" by providing education. The chief scientific officer of the Center, Nicholas Dodman, says coprophagy in dogs might also be learned from mom (Langley, 2015).

Another household pet is known for eating number two: rabbits. Their motivation is not, of course, wolf ancestry. Instead, it's having a second go round at nutrients. Rabbits and their kin (lagomorphs) produce two different types of droppings. The hard, round kind get left behind the bunny. Because rabbits, hares, and pikas eat mainly plants and plants are super hard to digest, they can divert food into an inner digestive pouch, where microorganisms do all of the hard work. Once the tough plant fibers have been digested, they are excreted in moist form, which the rabbit then eats so it can get all of the tasty vitamins and minerals.

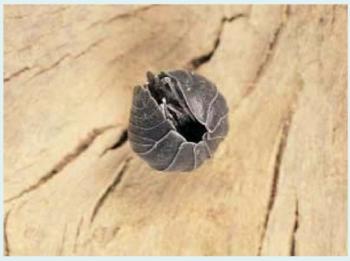

There are much smaller critters out there who dispose of dung for us. One that should immediately spring to mind is dung beetles. There exist several different, unrelated beetles who utilize dung, but they're all lumped together under the term "dung beetle." You may have seen them rolling balls of poo many times their own size along with their back legs. What's their fascination with feces? Some of these beetles use dung as food storage and some raise their young inside a dung ball. You see, by the time an animal like a cow or an owl gets around to depositing the digested remains of its latest meal, they may not have completely digested all there is to digest. In a way, it's like the rabbit who's breaking down those extra nutrients that didn't get absorbed on the first trip through the body. It's just someone else's body who did the first cycle of digesting.

A dung ball may not seem like a choice location for bringing up a brood of youngins, but these insects' behavior actually benefits us in important ways. By burying dung balls in the dirt, they help return nutrients to the soil. Some plants have seeds that don't get digested by other animals. So, by being buried as part of a dung ball, they get planted. Dung beetles are part of nature's cleanup crew. They take away the stinky piles that attract flies and other parasites that can make bigger animals like cows sick. Their efforts may seem tiny, but they benefit agriculture to the tune of over $380 million a year in the US alone (Losey, 2006).

What are smaller than beetles but love manure just as much? Fungi! While the kingdom of fungi is vast and diverse, a segment thrives on animal feces. One great example is a group known as "hat thrower" fungi and they're the fastest living organisms on Earth. They start out as spores in the grass. They're transported to a cow's digestive system when the animal is grazing. Then they're passed out of the cow in its poo. They use the poo nutrients to grow and develop spores of their own. Since cows don't like to dine too close to where they use the bathroom, the fungi have to get those spores as far away from the pile as they can. So, using water pressure, they fire those spores off into the grass at an amazing 180,000 g (Yafetto). By contrast, a fighter pilot's max is 8 g.

As far as the human consumption of our own bodily waste goes, these days, it's mostly relegated to fetishists and the mentally disturbed (I won't horrify you by detailing all of the accidental consumption of poo that goes on, I'll just say that it does go on). In the recent past though, doctors would taste their patents' stool samples as a diagnostic tool. Eating more than just a taste has been touted as a medical remedy, especially in Korea's past. In fact, consuming caca is still being used in medical treatments today. The practice is called FMT - Fecal Microbial Transplant - and it's an effective way to treat many digestive problems. Of course, the treatments come in the form of freeze-dried samples or pills, and donors are screened heavily (Wagner, 2016). FML is sort of an old-school remedy that's experiencing a resurgence in updated fashion.

Number two isn't usually our number one choice when it comes to conversation. It's kind of silly, actually, considering the sheer volume of it being created every day. In most situations, coprophagy is not healthy for humans, but we seem to be one of the few animals that don't benefit from it. A big reason we invented plumbing is to get our waste away from us with a quickness. There's a great article in Slate about our relationship with sanitation that does a good job of putting things in perspective (by Rose George https://slate.com/technology/2008/10/why-i-wrote-a-book-about-human-waste.html). I'm not personally a fan of coprophagy. In fact, I like to keep my bathroom habits pretty close to the vest. I am, however, interested in the more bizarre end of the spectrum when it comes to human behavior. Couple that with my love of shedding light on the commonly misunderstood and you've got yourself one article about poo.

Image: Adonis Blue butterflies by William M. Connolley (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Adonis_Blue_butterflies.jpg)

Sources:

Hart, B. L., Hart, L. A., Thigpen, A. P., Tran, A., & Bain, M. J. (2018, January 12). The paradox of canine conspecific coprophagy. Veterinary medicine and science, 4(2), 106–114. doi:10.1002/vms3.92

Langley, L. (2015, May 9). Why Do Animals - Including Your Dog - Eat Poop? National Geographic, Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/05/150509-animals-dogs-feces-health-science-dung-beetles-food/

Losey, J. E.; Vaughan, M. (2006). "The Economic Value of Ecological Services Provided by Insects" (PDF). BioScience. 56 (4): 311–23. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[311:TEVOES]2.0.CO;2.

Yafetto, L. et. al. (2008, September 17). The Fastest Flights in Nature: High-Speed Spore Discharge Mechanisms Among Fungi. PLOS One, Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0003237