Users Who Spiked

PRICKLES AND POKES AND PLANT PROTECTIONS

Private Notes

Private Notes

Notes

It's a Thursday evening in April and I'm seated in a remarkably comfortable folding chair in the Denver Botanic Gardens. About a hundred people in this conference room are either seated around me or finding their way to one. We're all waiting to see author Amy Stewart, who's here in Colorado to promote her book Wicked Plants: The Weed That Killed Lincoln's Mother and Other Atrocities. As a budding plant biologist, I can't wait to hear about the villains of botany. After about ten minutes, she appears, accompanied by an enthusiastic round of applause.

It is on this day in 2011, that I learn something that's stuck with me ever since. Stewart, slideshow remote in hand, informs us all rather wisely that just because something is "natural" doesn't mean it's good for us. To drive this point home, she clicks to the next slide, which is a photo of her standing near a very tall tobacco plant. She relays the story that goes with the picture of how, one day, she was driving past a tobacco farm and decided to pull over and have a look around. Within minutes of touching the leaves, she says, her arms began to go numb. The leaves of the plants were so potent that all she had to do was rub against them to lose feeling from fingers to elbows.

Tobacco produces chemical toxins on its leaves. One of them is called nicotine. Coffee produces caffeine which, even though most of us consume it on a regular basis, is also a toxin. Add to that potentially deadly plants like poison oak, belladonna, and oleander and you've got the start of a compendium of wicked plants. Plants, of course, lack the ability to get up and run from their predators. Can you imagine your leafy garden cabbage pulling up roots and scampering away from the neighborhood deer? Since locomotion isn't an option, plants have adapted other ways to defend themselves.

Toxic compounds are one defense mechanism. Nicotine, caffeine, strychnine, and digitalis are all plant-produced. After a lot of risky trial and error, we've been able to harness small doses of these chemicals for medicinal and recreational purposes. Strychnine was once given in pill form to treat human ailments, but now we use it mainly as rat poison. Digitalis comes from foxgloves and is used in heart medicines. But, if taken in too high doses, all of these chemicals are deadly. If you were to take a great big bite of a foxglove plant, you might just croak on the spot. Other plant compounds just taste bad, causing potential predators to spit them out and not come back for seconds.

Some plants have more obvious defenses. The honey locust tree (Gleditsia triacanthos), which is pictured above, has wicked-looking thorns. Many species of roses, of course, have prickles (not thorns). The kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra), in addition to being very tall, has a trunk covered in cone-like thorns. Even sunflowers (Helianthus annuus), which seem fairly harmless, have hairlike trichomes that irritate the skin of anyone trying to pick one. Nearly all cacti have spines that not only protect them but help them retain water. Thick bark and impenetrable cuticles are less dangerous to predators but still serve as armor against parasitic attack.

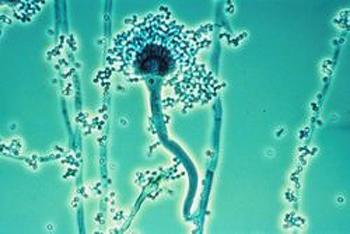

And recently, scientists are discovering yet another way in which plants defend themselves - communication. I met a scientist once who injected purple dye into a tree in an orchard. Within a day or two, at the other end of the orchard acres away, she cut open another tree and found it was purple inside. How'd the dye get from one tree to the other? Through something that's being dubbed Nature's internet. Instead of wires, it's fungi that form this information superhighway. Plants can transport water, nutrients, and other chemical signals through the fungi to each other, sometimes helping each other out and sometimes sabotaging their neighbors.

How does this act as a defense? Say a bunch of tomato plants are hanging out in a garden. One unfortunate plant gets infested by aphids. That tomato can send out a message to the others, warning of attacking pests. When the other plants receive the message through the network of fungi fibers, they start producing chemicals that fight off aphids. Those plants, then, are more successful at repelling the tiny predators.

This opens up a whole new way for us to look at plants. There's a lot of research to be done in this arena, a lot of new questions to be answered. Why do these plants warn each other? Is it altruism or just stress? What other signals are the plants sharing and what information do those signals carry? While it's important to keep perspective and not anthropomorphize their motivations, it's certainly enough to make me think the movie, The Happening is a little more haunting.

Read more:

What's the difference between spines, thorns, and prickles?

https://www.arboristnow.com/news/thorns-and-prickles-and-spines-oh-my-

Tree communication strategies:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-whispering-trees-180968084/

Fungi communication network:

http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20141111-plants-have-a-hidden-internet